The Wrong Exit

How Germany dismantled its own energy spine — and drifted into the orbit of a petro-state

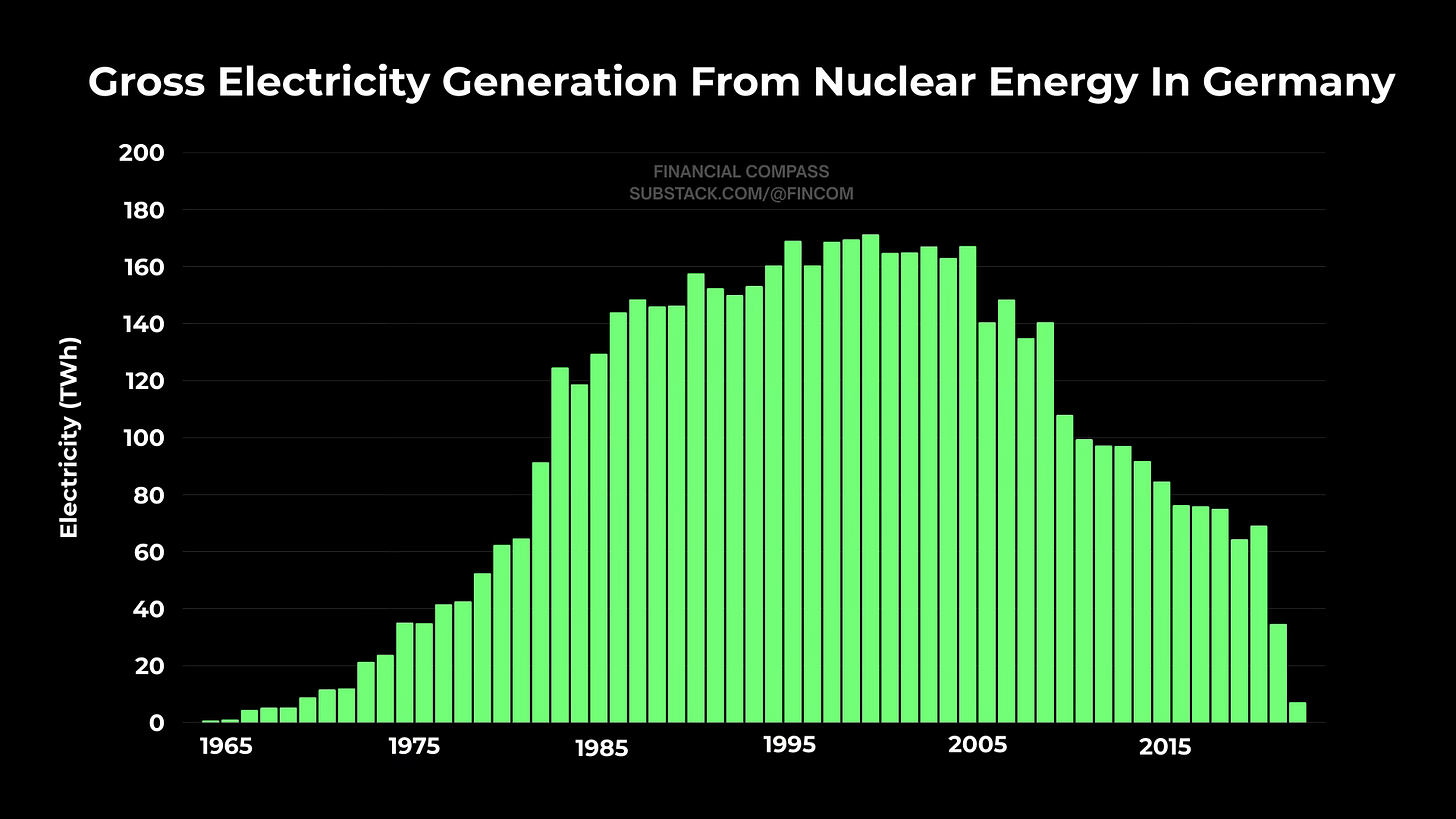

Germany once possessed one of the cleanest, cheapest, and most reliable nuclear fleets on Earth. More than 20 gigawatts of amortized capacity, a solid, dependable source of power. And yet, across fifteen years, Berlin dismantled it almost to the bolt, leaning instead on a pipeline to the east that carried not only gas but geopolitical risk.

This is not about ideology. It is simply the logic of what happens when a nation amputates a functioning limb and then depends on the man holding the tourniquet.

By 2000, Germany operated over 22 GW of nuclear capacity. The reactors had long since paid for themselves; every megawatt-hour they produced arrived at almost frictionless cost. No soot, no volatility, no geopolitical strings.

Then, in 2010, came the political season of Energiewende — an energy transition framed as moral duty, aesthetic preference, and industrial ambition. Angela Merkel, one of its chief political architects, insisted the shift was both inevitable and desirable. She stated:

“We want to end the use of nuclear energy and reach the age of renewable energy as fast as possible,”

It increasingly appeared that the dismantling of nuclear power was driven less by a sober assessment of risk and more by a political reflex, a fear of incidents rather than a calculation of consequences. The country treated the nuclear plants as a liability, not as a strategic asset, and in doing so severed one of the most stable pillars of its own energy architecture.

After the Fukushima accident, the phaseout accelerated. Eight reactors shut in 2011 alone — nearly 8 GW erased in one sweep. By 2021, only 8 GW remained, and by 2023, the dial hit zero.

A Drift into Russian Dependence

Angela Merkel intended to replace nuclear power with renewables, but Germany is neither particularly sunny nor consistently windy. The strongest wind resources are offshore, not inland, and even today wind accounts for only a modest share of total energy demand. Solar performs unevenly across the year and cannot provide firm capacity.

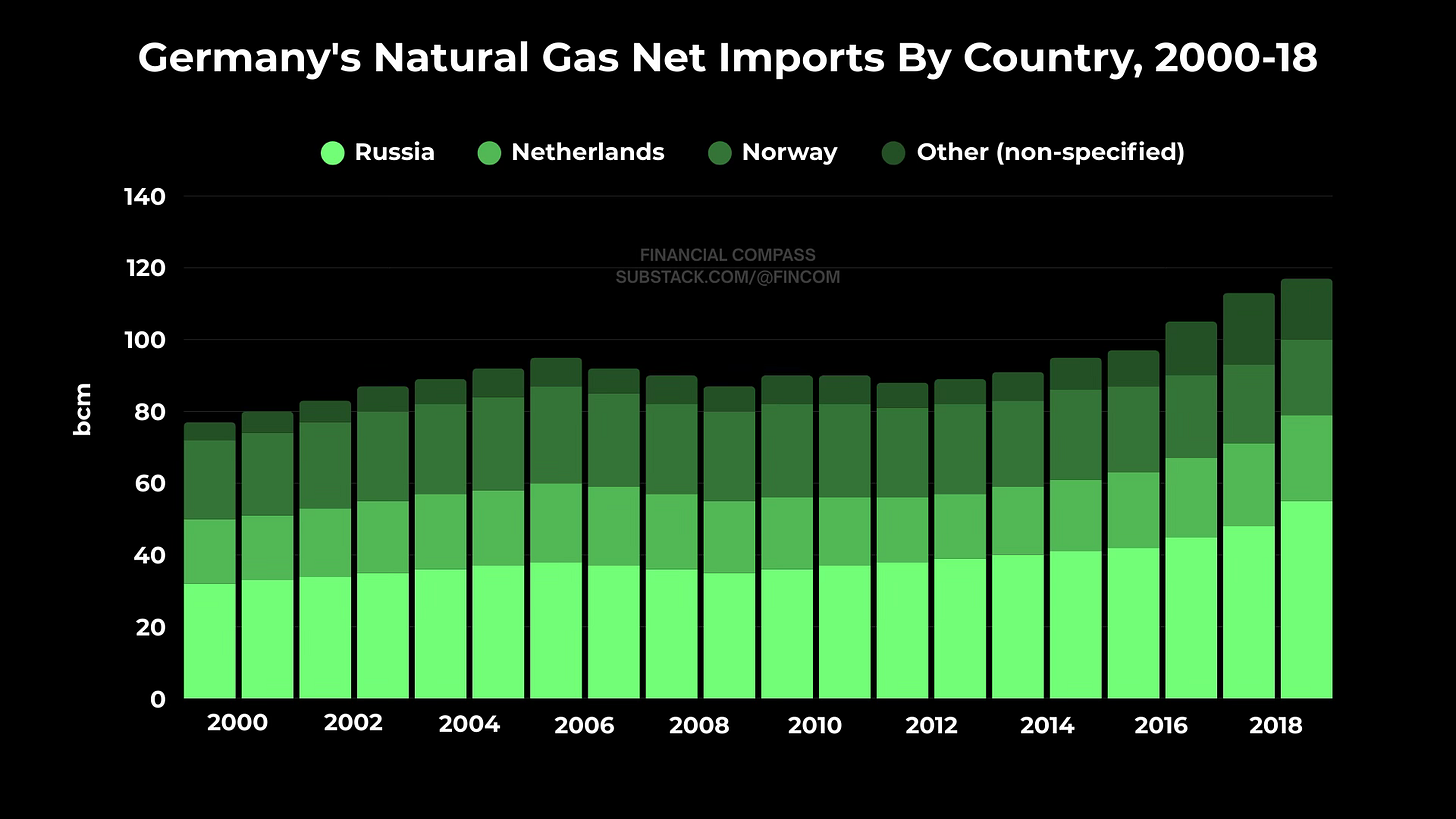

As a result, renewables could not replace baseload generation, and the gap had to be filled by something else. That structural limitation is why Germany remained heavily reliant on natural gas.

From 2010 onward, the trend is unambiguous. As Merkel’s Energiewende advanced and nuclear capacity was phased out, Germany covered the shortfall with imported gas.

Merkel’s “double switch” compounded the problem. As nuclear was wound down, subsidy cuts and shifting regulations undercut Germany’s own photovoltaic industry just as global solar manufacturing was scaling up. What could have become a competitive domestic pillar of the transition was weakened instead, leaving Germany even more dependent on imported hydrocarbons.

A significant share came from the Netherlands, but that path closed in 2023. The Groningen gas field, one of the largest in the world, was shut down in after years of extraction triggered soil subsidence and repeated earthquakes. What had been a major regional supply source was phased out by the Dutch government, removing another option just as Germany’s own baseload was disappearing.

The largest share had always come from Russia. When Berlin stepped away from nuclear power in 2010, the gap didn’t stay empty; it was filled year after year by rising Russian volumes. By 2018 the pull was clear, just over half of Germany’s imported gas came from a single source, a share large enough to expose how unbalanced the system had become.

In 2018, the construction of Nord Stream 2 had started, with the goal to double the flow of Russian gas into Germany and bypass transit states entirely, ironically to be less dependent. The line was completed in 2021, presented as a commercial project, but it locked the country even further into a single supplier. It had consolidated risk rather than reduced it.

In the same year the project began, Donald Trump met with NATO and German representatives and was strikingly direct — and, in hindsight, very accurate — in an exchange with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg:

“Well, I have to say… I think it’s very sad when Germany makes a massive oil and gas deal with Russia. You’re supposed to be guarding against Russia, and Germany goes out and pays billions and billions of dollars to Russia. So we’re protecting Germany, France, all of these countries, and then many of the countries go out and build a pipeline and make a deal with Russia, where they’re paying billions of dollars into the coffers of Russia.

I think that’s very inappropriate. And the former Chancellor of Germany is the head of the pipeline company supplying the gas. Ultimately, Germany will have almost 70% of its country controlled by Russia through natural gas.

So you tell me… is that appropriate? I’ve been complaining about this since I got here. It should never have been allowed to happen. Germany is totally controlled by Russia, because they will be getting around 60 to 70% of their energy from Russia and a new pipeline.”

By autumn 2021, the warnings about Russia’s mobilization were public. Satellite photos circulated, and analysts mapped out invasion windows. Western intelligence spoke openly. And yet Germany stayed the course: 4 GW of nuclear capacity scheduled for December 2021 closure would still close. The remaining 8 GW capacity would still shut the following year.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the Nord Stream 2 certification was halted immediately. On 26 September 2022, the pipeline was sabotaged, and the perpetrator has still not been identified. It never delivered gas, but the dependence it represented was already firmly in place, and the €9.5 billion project now stands as one of the most expensive dead ends in Europe’s energy policy.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe for free to Financial Compass to get new articles delivered straight to your inbox. 📥

A System With No Margin

Germany’s nuclear fleet produced around 160 TWh a year. Replacing that output with gas-fired generation would require roughly 280 TWh of natural gas — more than double what Germany typically used for electricity production. While small relative to national gas consumption, this shift reshaped the power sector and increased dependence on imported gas.

In the winter of 2022, that missing share would have materially altered both the energy balance and the political leverage surrounding it. The energy crisis of 2022 is often blamed on Russia alone. The truth is simpler: Germany designed a grid that could hardly survive a geopolitical shock.

Industries built on stable energy — chemicals, metals, fertilizers — found their margins vaporized. BASF, the largest chemical company in Europe and a German industrial cornerstone, announced broad reductions across its European operations, especially cutbacks in Germany. The company was widely seen as the biggest corporate victim of the energy crisis, its flagship plant alone consumes as much natural gas as Switzerland. Its CEO, Martin Brudermüller, stated:

“These challenging framework conditions in Europe endanger the international competitiveness of European producers and force us to adapt our cost structures as quickly as possible and also permanently.”

The irony is that renewables were meant to grow while nuclear provided the bridge. Instead, nuclear disappeared first, gas moved in to cover the shortfall, and renewables expanded inside a system that no longer had a stable floor beneath them.

Coal, the very fuel Germany vowed to expunge, made a comeback in 2022, shortly after the Russian invasion in Ukraine started. Reuters reported:

“Germany is planning to use coal-fired power stations which would have been idled this year and next as reserve facilities in case of disruption to gas supplies from Russia.

Gas … must be prioritised for industry and heating homes if a bottleneck arises, making it necessary to draw on idled coal capacity to fill the gaps.”

Immidiately, a wind project beside the Garzweiler open-pit mine was being dismantled to expand lignite extraction. At the same time, Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced that five lignite-fired power plants will be brought back to life.

The timing made the situation unmistakable. Within weeks of the invasion, Germany found itself facing an acute energy shortfall. Coal, one of the dirtiest fuels Germany had spent a decade promising to eliminate, was immediately brought back into the system.

It was a direct reversal of Merkel’s Energiewende, a project built on the premise that the country was steadily transitioning toward cleaner sources. The emergency measures exposed how little margin the transition actually had.

The Aftermath

Now, in 2025, the panic has faded, but the design remains the same. Gas prices are lower, yet Germany still lacks firm capacity and still relies on imports to keep the grid steady. Renewables continue to expand, but expansion is not stability; without a dependable baseload, the system carries the same structural exposure that broke it the first time.

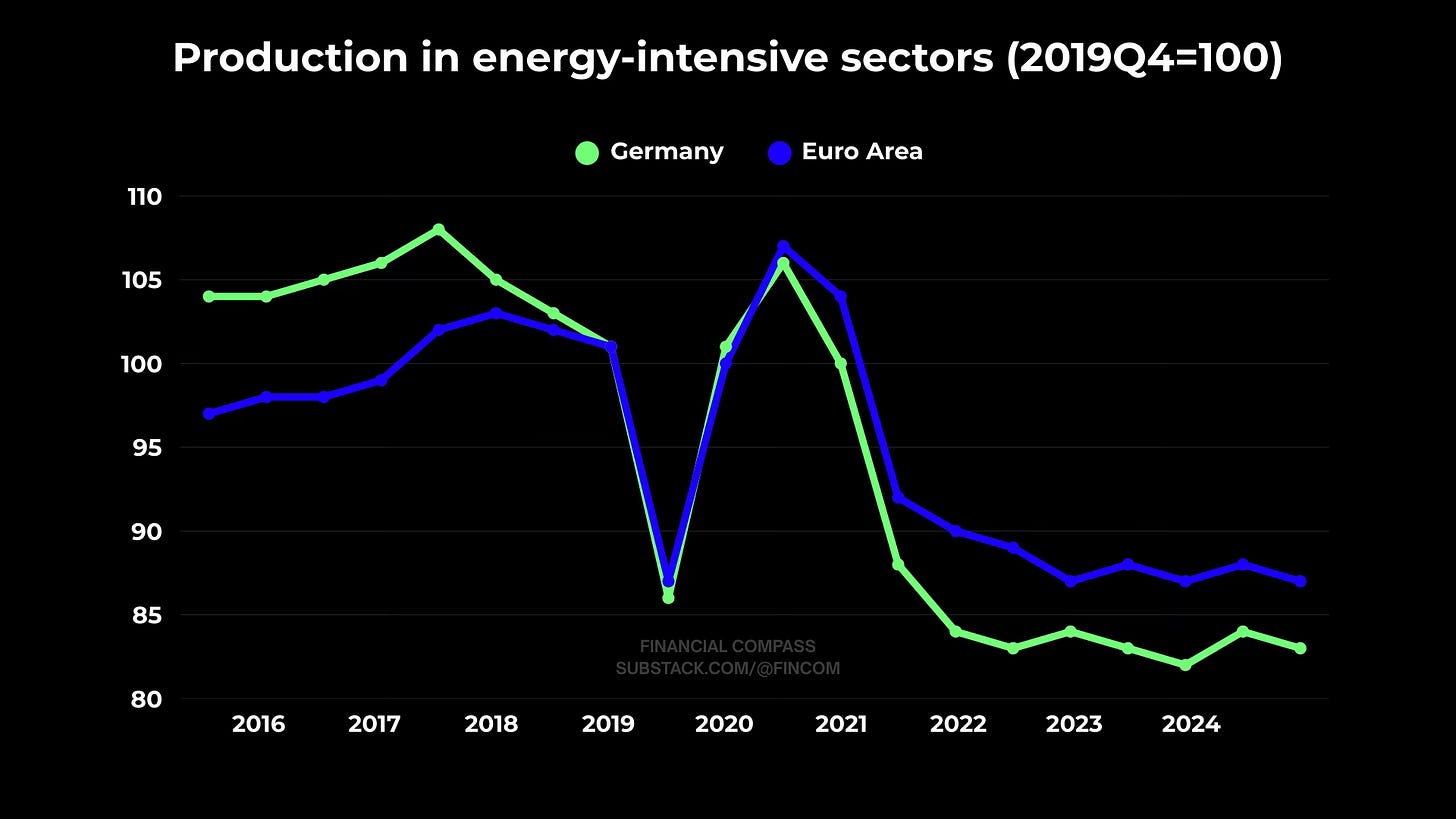

Germany was hit harder than the rest of Europe. Its energy-intensive industries contracted sharply in 2022, and output has lagged ever since. Even today, German production sits below the euro-area average, a gap that has not closed. Industrial activity remains subdued, energy-heavy sectors are still cautious, and investment continues to drift abroad.

Germany’s first mistake was shutting down nuclear power, the one source that offered stable, low-cost, and clean capacity. The second was filling that gap with natural gas and allowing an outsized share of it to come from Russia. When pressure arrived in 2022, the structure failed immediately: industry slowed, coal returned, and the country learned that its transition had rested on the assumption that Russian gas would always be available.

Some analyses suggest that if Germany had kept its nuclear fleet running from 2002 to 2022, it could have cut its carbon emissions by roughly 70% and avoided hundreds of billions of euros in energy-transition costs.

Nuclear power offered Germany exactly the kind of steady, clean support that could have carried the country through the hardest year of its energy crisis…

An interesting perspective, Financial Compass!

Shortly after the reunification in 1989, I wrote a book about Germany, titled “The Vulnerable Colossus.” After the horrors of the Holocaust, Germany has remained an insecure country.

In fact, it used 1989 to embark on a long “holiday from history.” It made its economic success and political stability dependent on gas from Russia, cheap products from China, and a security umbrella from the United States — recently adding the phase-out of nuclear energy without having a robuust and credible alternative.

In October 2022, I argued in an analysis that Germany and Europe must above all remain vigilant regarding the United States. Its view of the world is instrumental and power-oriented. It acts as a gatekeeper, using its power to make others do what it considers right —this applies not only to its adversaries, but also to its allies in Europe and elsewhere. This power is built on access to available resources such as raw materials, on technological and military superiority, and on monetary dominance, with the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

I think we are currently witnessing the accelerated rollout of that policy, more than ever.